Reed’s Refuge Center continues to be a beacon for Wilmington’s Eastside youth

For nearly two decades, Frederick and Cora Reed have dedicated themselves to uplifting youth in one of Wilmington’s most challenging neighborhoods. In 2012, after successfully running several childcare facilities, the Reeds again stepped up to support the youth of Northeast Wilmington. They created — as they say — a “diamond in the rough” called Reed’s Refuge Center (RRC), located at 1601 N. Pine Street.

Many Reed’s Refuge constituents come from precarious, sometimes perilous, circumstances. Of its attending students, 100% are considered at-risk, with more than 60% being raised by a single parent.

“Our community’s youth needed a safe haven to be able to express themselves in a positive way and discover their hidden talents and gifts,” says Cora. “We wanted them to express that creativity through the arts, whether singing, dancing, rapping or acting. [Reeds Refuge] gives them an escape from guns, drugs, violence and teen pregnancy.”

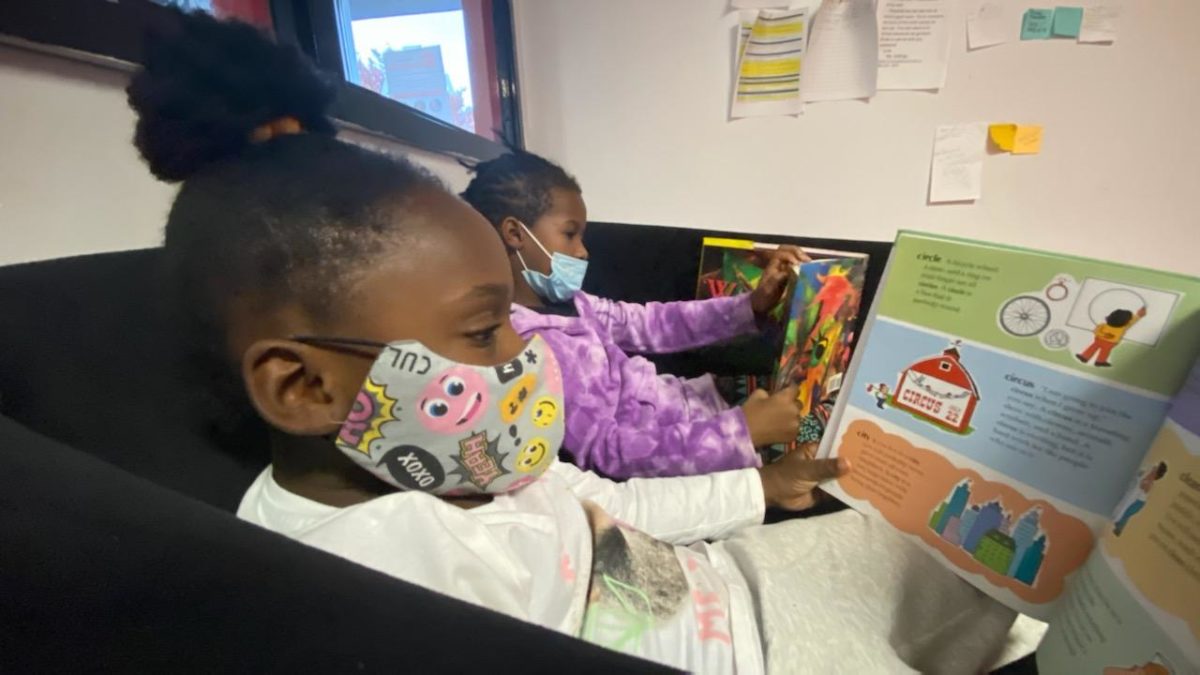

Since its inception, RRC has provided an inner-city sanctuary to more than 1,000 youth, and its programs boast a hearty 85% retention rate. The average student age ranges from 9 to 13.

“One of the things I’m thankful for at Reed’s Refuge is that Mr. Reed and Mrs. Reed make me feel like I got another home here,” says 10-year-old Ahmere Jones, who has been a student for almost four years.

Life (Skills) As Lessons

RRC’s curriculum is heavily arts-focused — think music production, dance, graphic design — but it also incorporates STREAM (Science, Technology, Reading, Engineering, Arts, and Math) programming as well as life-skill classes.

Dajahnai Ross, age 16, has attended dance, music production, and other courses at RRC for eight years. “The staff here helped me with my work…and [taught me] to never give up even if it is hard,” she says. “As one of the older kids, I was assigned to be a peer leader, which meant helping the younger children with their homework and being a mentor.”

One of the classes Reed’s young charges embrace is “Cooking Without a Stove,” Cora says. This four-to-six-week culinary course, led by Chef Oshay Lolley, teaches kids to prepare healthy meals solely via microwave.

“Their favorite creations include pasta, fish, juice smoothies, and baked potatoes,” Cora says. “Who doesn’t love a fluffy microwaved baked potato?”

Reed’s budding young chefs have also prepared and delivered meals to Wilmington’s homeless population.

When asked, Frederick notes that RRC’s most popular programs revolve around music-making. It’s no surprise that music would be a major offering. Frederick has experience in the music business, performing on national and international stages and opening for such notable artists as Mary J. Blige, Run-DMC, Keith Murray, and Big Daddy Kane.

The audio engineering programs, he says, provide a creative outlet for youth who may feel “stuck.” It gives them hands-on experience with a genuine state-of-the-art studio, learning how to record, mix and master their own songs.

“Coming from Riverside, many really don’t get to experience leaving the projects,” says Frederick. “I figured if [music] gave me an outlet, how many other youth could use it as a tool to escape poverty, violence, and more?”

In a recent video on the organization’s Facebook page, a 16-year-old student settled in behind the soundboard, head nodding to the music being created in the booth by a quiet but focused young boy. The youngster happily raps along to the music, singing about going to school, getting A’s, playing outside. A round of cheers erupt as he finishes his track, and you just know that adulation is led with pride by Frederick.

“We also teach [our students] to be creative entrepreneurs; many of our students have designed their own t-shirts, clothing, business cards,” he proudly notes. “Students have created most of the art you see on our walls.”

And students of RRC are delighting in these skills at no cost to them.

“I like Reed’s Refuge Center because I can play and spend time with friends, and it’s fun,” says 8-year-old Nasir Taylor, who has attended RRC for four years. “I also like to make shirts with my name on them; that’s my favorite part.”

How do the Reed’s gauge the impact of their work? “Success comes in many forms,” says Frederick. “A lot of our youth are getting better grades now, helping our community as great youth leaders. They’re becoming productive citizens.”

A.J. Harding, a mentor and counselor at RRC, sums up why the organization is critical to Wilmington as a whole. “[Reed’s Refuge] is important because it serves as a beacon of light that gives hope to our community, but it brings a sense of unity as well.” He references a quote used often at RRC: “We do it better together.”

Reeds Refuge as a Balm for Community Healing

Although programming has been challenging during the pandemic, RRC looks forward to reviving some of the programs they saw previous success:

• Before COVID, Music Production students recorded a compilation CD of 9-10 songs that gave them a chance to speak out against social injustice.

• Just before the shutdown in 2019, RRC’s Youth Against Violence program hosted a livestream forum event. Connecting teens with their peers and healthcare professionals, the discussion engaged them in provocative topics like depression and anxiety, gun violence, and teen pregnancy.

The greatest challenges the Reeds see with youth in their community are mental and emotional issues, hunger, lack of rest, and the need to be loved and nurtured.

“We deal with a lot of behavioral and mental health issues,” says Cora. “One obstacle is, we only have [these students] for a few hours; if the parents get involved and learn some of the same things we’re teaching our students, it would make a great impact.”

The organization’s evolution will enable them to significantly increase their reach in the immediate neighborhood and beyond, as well as broaden services not only to youth but their parents as well.

“We’ve seen the struggle of parents and heard the cry,” says Cora. “We want to be able to service the entire community, and ideally, for free.” That means, she says, offering things such as counseling, finance, and life-skills classes for parents as well as their children.

One of the services RRC is hoping to augment is its therapeutic room. Launched last fall, this bright, cheerful space connects mental health therapists with students. Right now, the sessions are only referral-based, but RRC is hoping to expand the program to include counseling for parents as well as additional students on a regular basis.

Critical Funding Still Needed

As co-founders and executive director and chief financial officer, respectively, Frederick and Cora have, up to now, poured much of their own finances into Reed’s Refuge.

“This is what we believe in, and this is what we’re investing in,” says Cora, who along with her husband, is a lifelong Wilmingtonian — Cora from the West Side, Frederick from Riverside. “We understand the people here, what they’re going through. We can relate to them; we’ve been a part of it.”

So, the Reeds are pursuing their next goal: Expanding Reed’s Refuge from its current footprint of 6,000 square feet to 28,000 square feet. While some capital for the buildout has been raised, the couple is seeking additional funds from corporate support and national grants.

“We’re right in the backyard of many major banks and corporations,” they say. “Support from any of them would be so impactful, but it’s been difficult because we’re seen as the new kids on the block.”

In the coming months, they plan to have architectural renderings and a video “pitch” available for potential funders and investors. The site blueprints detail enlargement of each math, science and reading classroom; extension of a Zoom conference room; addition of a master studio; theater for live performances; graphic design studio; commercial kitchen; dance studio.

The Reeds hope the project can be completed by the end of this year. Going forward, they’d like to see the Reed’s Refuge ‘model’ replicated statewide.

“Our overall goal is to just instill hope,” says Frederick. “It’s not about where you come from; you just have to be willing work hard and persevere.”